Navigating versus Journeying: Brief Reflections on my PhD journey (part 1)

Things felt best when I wasn't going anywhere — they felt best when I knew things were going well

One of the biggest tropes of the PhD program is that it is a journey. Sisyphean. Hard. Marathon. Not all who start will finish. At the time, I certainly appreciated this framing, reminding me that my annoyances were just that — side stitches should not disrupt my forward progress. In marathons you follow a prescribed route, along mile markers, often with cheering crowds a several points, all towards a concrete finish line. As a navigational challenge, the hard part is “just” putting one foot in front of the other. If you can do that some would say that the rest is fairly trivial. But it’s not.

How we conceptualize our movement through space biases where we end up. And there are other ways of viewing a PhD as an act of navigation other than a marathon. The beautiful thing about learning about other ways of journeying is that they may not be just techniques but whole ways of being.

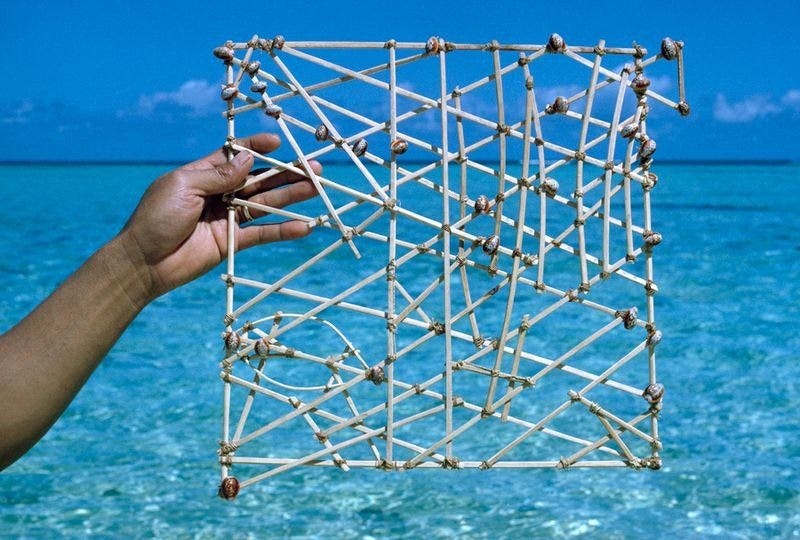

I first found out about Polynesian seafaring in a wide ranging adviser discussion over indigenous knowledge systems and databases. In community-based economies work Indigenous and local knowledge systems are not only examples of valuable community methodologies, their significance self-evident through history without requiring RCTs, but they help situate and contextualize the knowledge and questions that you — our researcher — hold now.

Process or a Destination?

In 1976 Mau Piailug — trained from birth and mentored by his grandfather Raangipi, later on by his father — sailed without instruments from the Carolinian islands to Tahiti, a distance of over 450 miles. Together with the Polynesian Voyaging Society, Mau’s journey contributed evidence to the field of experimental anthropology that not only was Polynesian migration over vast water ways possible, but it was intentional. Like medieval guilds of thousands of years ago, the PhD program is largely carried out under a master-apprentice relationship, where a master instructs and demonstrates to the apprentice how to craft masterpieces, or accepted papers, while the student provides their labor, as a research or teaching assistant. The student demonstrates their achievement through a magnum opus, or a thesis — but a first author published paper would suffice, philosophically speaking. The relationship between Mau and other Palu, master navigators, on his own journey to become Palu, was different.

Here way finding is in many ways analogous to an ongoing sensory process, with continual checks and memory references. Cultural stories and natural markers intertwine. The stars, the waves, the reflections of clouds, echoes of their adviser's instruction, are present at the ear, on the tactileness of the skin, as the craft moves, while continuously remembering. What did the waves look like yesterday? What do they look like today? Where were the stars at dusk? The focus is less on where they go, less about milestone markers, and more on how to go; one could way find their way to the academies, to industry, to Maui, or to Kauai. This contrast helps us see where systems of navigation are more like journeys and where they are less like one. For myself, the idea of Polynesian way finding helped put another kind of navigation, the PhD program, into a different context

I only had a few "aha" moments during my PhD program but they were pivotal, changing how I worked and thought each time. I got by through repetition based refinement that gradually became clearer, better, and stronger, through responses from the academy — largely my advisers at this point. Perhaps my biggest “aha” was through talking with a director. I was asked how things were going.

And I realized, as a developing academic, that things felt best when I wasn't going anywhere. They felt best when I knew things were going well. It felt best when navigation felt more like a journey than a destination, by acting from an internal guidance system, with support from others, as I made my way.

In this less related to community-based economies series, I want to commit to writing a smorgasbord of references, tips, and thoughts that were helpful to me so that they may be helpful to others. My next post will discuss my experience with goal setting and adapting to changing circumstances and priorities.

[T]hat things felt best when I wasn't going anywhere. They felt best when I knew things were going well.

Note: You can read my day to day thoughts and work in my daily notes here.

This is so beautiful in so many ways. It's time to remember the ways of our ancestors, no matter the culture. We can all learn to navigate again.

Love the indigenous knowledge intro!